News

Mai Ka Pō - Return to the Source

Malia Evans works in education and Native Hawaiian outreach at Mokupāpapa Discovery Center on behalf of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (PMNM) and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation (NMSF). The monument encompasses over 1,200 miles of protected ocean, islands, atolls and shoals. In July 2019, she joined three other wāhine (women) researchers on a 12-day scientific expedition to deploy and retrieve acoustic moorings and sensor equipment from various locations in PMNM. The following articles are a daily reflection of her first ever journey into the Kūpuna Islands (ancestral lands) of Papahānaumokuākea.

Lā ʻEkahi (Day 1) July 12, 2019

He ʻike makawalu kaʻu e ʻanoʻi nei. I yearn for the deep knowledge.

The morning dawns bright and clear as I triple check my gear for this huakaʻi (voyage). Iʻm super excited but alternately fearful of being at sea for 12 days. Iʻve never been on a boat longer than 6 hours and every single trip on a motorboat has resulted in major seasickness. However, Iʻm fully prepared with vials of Bonine, Dramamine, and everything ginger including tea, gum and chews. Wrapped securely on my wrists are Sea Bands pressing my P6 acupressure points. I pop 2 Bonine tablets an hour ahead of departure, eat soup and drink lots of wai (water). I am ready. Our scientific team meets up at Kewalo Basin to load our personal gear on the Searcher. Chief scientist on board is Eden Zang, Research Specialist with the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary (HIWNMS). Graduate students Brittany Evans and Paige Wernli are with UH Mānoaʻs Hawaiʻi Institute for Marine Biology (HIMB). My background is in archaeology, ethnography and education and Iʻll be documenting the research mission through photos, videos and journal entries. After a safety briefing with Captain Jon Littenberg, we cast off and head out of the channel as surfers ride 2-3 foot waves rolling in from the south. The ocean is mālie (calm) as we head northwest in the lee of Oʻahu but within hours choppy seas and blustery winds mark our transit through Kaʻieʻiewaho Channel.

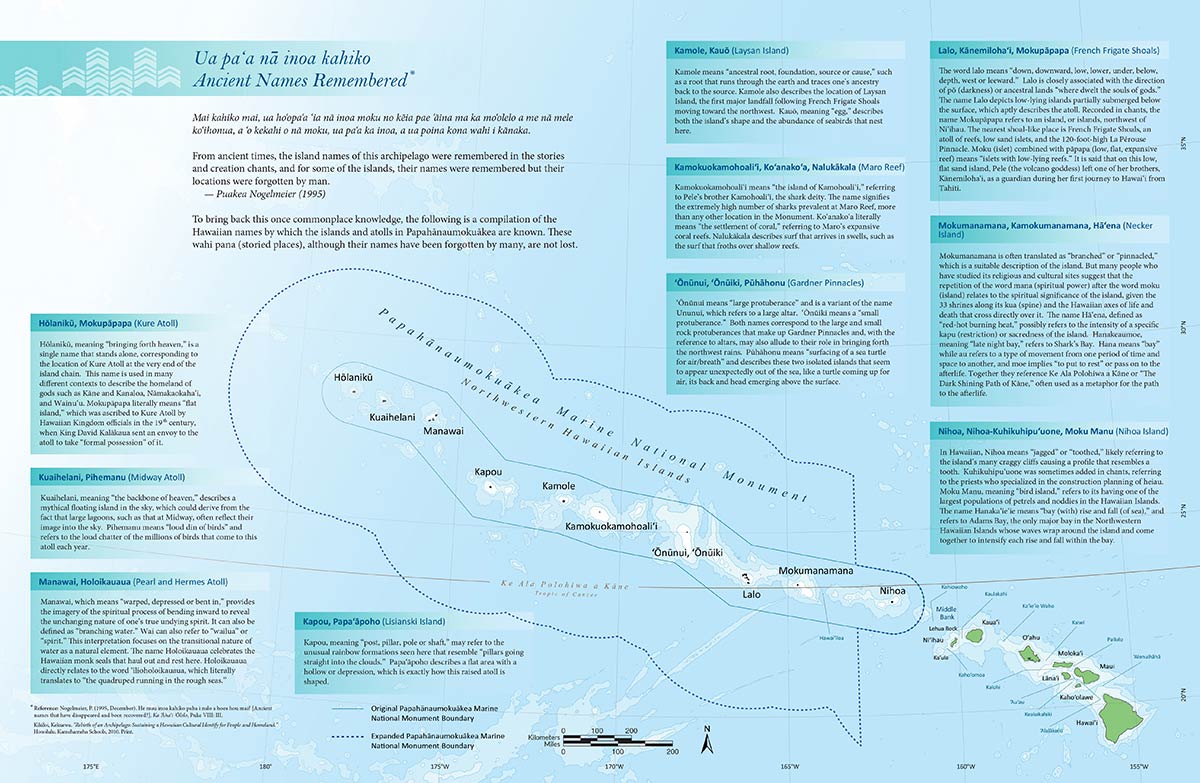

The oldest, northwesternmost islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago are known as the Kūpuna (elders) Islands. Inherent in this Native Hawaiian worldview is the kinship relationship that Kānaka Maoli (indigenous people) maintain with these ancestral lands and oceanic domain. Generations of oral histories, genealogies and place names document the importance of these islands, atolls, shoals and seascapes to the native people of Hawaiʻi nei.

As the sun plunges below the horizon we gather for dinner. Iʻm stoked I can eat on a ship. Thatʻs a first. As darkness settles, I head to the flybridge to gaze at the heavens. Itʻs a Huna moon and Nā Hiku (Big Dipper) is rising off starboard. Kauaʻi is a soft, amorphous shape hidden in clouds, with occasional lights twinkling through. As we pass Kauaʻi we lose internet service on our phones. The time has come to tune out text messages, email, social media and various distractions. Itʻs time to tune in to the natural world. Iʻm yearning for that deeper knowledge.

Lā ʻElua (Day 2) July 13, 2019

Ulu aʻe ke aloha no Nihoa moku manu. Our respect grows for Nihoa, isle of birds.

Early morning light streams through my porthole, enticing me to come and see. Deep ocean surrounds us, pacific and lulling while a flock of seabirds fly low toward the north then begin circling a school of fish. They fly effortlessly, occasionally skimming wingtips over the ocean's surface. Swells roll in from the east rounding against our starboard side as we transit closer to Papahānaumokuākea.

I feel healthy and strong as if the ocean is providing me energy so I remove the Sea Bands. I channel my voyaging ancestors and remind myself, “Iʻm a descendant of the greatest voyagers and navigators in the world”. That is my mantra for the rest of the journey. After a hearty breakfast we discuss techniques to deploy the first 2 acoustic recorders near Middle Bank and Nihoa. The passive acoustic devices will record underwater soundscapes to understand how much sound is introduced into the monument, what is producing those sounds and how it impacts specific marine organisms, including whales. This can help researchers understand the behaviour, abundance and distribution of humpback whales in PMNM.

When the prep or deployment of receivers is pau (finished), I hang out on the flybridge. I have a 360 degree view to kilo, to deeply observe the ocean surface, sky color, cloud formation, seabird species, wind speed, swell size and direction and marine life. I understand that marine debris is a huge problem in the Pacific. Iʻm surprised at the lack of ʻōpala (rubbish/marine debris) on the surface of the ocean. I wonder what ʻōpala lies below the surface? I do spy a floating object which turns out to be a glass fishing float. These floats can spend decades at sea caught in gyres, or rotating currents in the Pacific. Too bad I didnʻt have something to snag it with as the floats are valuable collectors items.

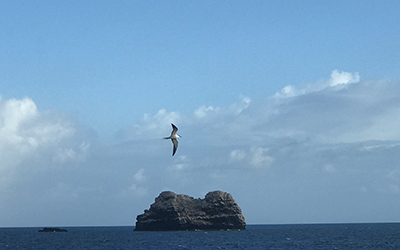

In the late afternoon, I see Nihoa off starboard, jaggedly fierce and jutting from the sea of Kanaloa like a tooth. I get chicken skin as I see a kupuna face revealed in the afternoon sunlight. Then I see another face in the clouds, gazing lovingly down at Nihoa. Hū mai ke aloha no ka ʻāina. Love for the homeland swells forth.

Nihoa has a rich cultural history with 89 archaeological sites including house platforms, ceremonial sites, agricultural terraces, shelters, cairns and burials. Three water sources supported a small population between AD 1400-1850ʻs. Artifacts recovered from Nihoa include stone jars, dishes, fish hooks, bird bone needles, a bird snaring perch, and coral rubbing stones.

Moʻolelo (historical accounts) from Kauaʻi and Niʻihau recall voyages to Nihoa to fish and gather subsistence items. Nihoa and itʻs environs continue to be important navigational training grounds for our next generation of voyagers.

Lā ʻEkolu (Day 3) July 14, 2019

Mai ka pō. Return to the source. (Hawaiian proverb)

The seas were calm last night, rocking me like a baby. Time has become strangely irrelevant. I calculate the passing of time by the sun's movement and meal times. Iʻm up early on the fly bridge doing my daily kilo when I discern a distinct glimmer on the far horizon. As we move nearer, I see the glowing fingers of rounded basalt as Mokumanamana rises from the deep. I ponder this spiritually significant island that contains over 52 archaeological sites and the highest concentration of heiau (religious temples/shrines) in Hawaiʻi nei. The stone structures include paehumu (platforms), paepae (terraces) and manamana (upright markers). Current research by Kānaka scholars is uncovering the brilliance of ancestral knowledge related to celestial alignments, voyaging practices, time calibration and religious ideology. Unique kiʻi pōhaku (stone images), not seen elsewhere in Hawaiʻi, were fabricated on island and once resided within the heiau structures until their removal in 1893.

As we transit closer to Mokumanamana, I watch the massive waves pound the forbidden cliffs, sending ʻehukai (seaspray) toward the highest elevations. I understand why the island was glowing. It was that ancestral brilliance.

The Hawaiian cosmogonic chant Kumulipo describes the birth of the universe and the myriad of organisms that evolved within it. The chant distinguishes two realms, Ao; a place of light where living beings reside and Pō; a place of deep darkness where life originates and eventually returns after death.

During the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, the sun transits directly over Mokumanamana. Lā (the sun) represents life and death in Hawaiian oral traditions and its journey from east to west a metaphor for the span of a human life. As we cross over from Ao to Pō, I am mindful and aware of kaona (deep, layered meanings) inherent in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language). While some may regard Pō as death, I innately understand my journey into Papahānaumokuākea is beyond just the physical. It encompasses more of an intellectual and spiritual journey…mai ka pō…returning to the source.

To learn more about Nihoa and Mokumanamana visit: www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/wheritage/archaeology.html.

Lā ʻEhā (Day 4) July 15, 2019

Manomano ka ʻike liʻu o ka houpō o Kanaloa. The deep knowledge of our Kūpuna lies in the

depths.

The days are melding. I donʻt need to know if itʻs Monday or Friday. What I do need to know is how to brace my body against the shipʻs surfaces, how to utilize a wide stance and dance nimbly across the floors of the ship as the ocean rolls beneath me. Iʻm learning how to flow with the rhythm and knowledge of the ocean and to experience this natural world thru my senses. Today I spy the usual gang of ʻā, brown boobies and red-footed boobies. One lands on the winch, perching and preening. Suddenly, it takes flight, plunging seamlessly into the ocean. It startles a single mālolo (flying fish) that darts above the surface then crash lands against a wave to escape its winged pursuer. At awākea (noon) I spy a new bird that rocks my world. Sporting a sleek white body, trim wings with a long red tail, a single koaʻe ʻula (red-tailed tropicbird) glides elegantly above the ship. These vignettes of life extend into the depths of the ocean as a pod of bottlenose dolphins leap gracefully along our port side for a brief moment.

I wonder at the diversity of unknown life that dwells in the mysterious depths of this ocean, this embodiment of Kanaloa. What knowledge can we learn through respectful exploration and research?

Lā ʻElima (Day 5) July 16, 2019

A Haiku poem I wrote today:

Glide into my view

Guardian of liquid depths

A mighty manō.

Up early as we will be arriving at Kamokuokamohoaliʻi (Maro Reef) during the early morning hours. The submerged atoll is named for Kamohoaliʻi, the eldest brother of goddess Pele. Kamohoaliʻi was a navigator and an akua manō (shark deity) who voyaged with Pele and ʻohana to Hawaiʻi. I head to the flybridge to greet the ancestors of this place with an oli. As I finish the chant, I see a solitary large manō (shark) glide effortlessly toward me while I lean on the port side rail. I gaze with wonder and gratitude at the large shark that disappears into the depths as quickly as it appeared, perhaps guarding his underwater kuleana. The largest population of sharks in all of the monument is found here. Encoded in the place name is cultural and ecological knowledge that references the abundace of sharks in this ecosystem. Passed down through the generations, place names remind us of this rich knowledge base. Later that morning, we spot two more large manō as we traverse the reefs looking for a previously deployed acoustic recorder.

Despite our morning long survey and transects the recorder remains elusive. Perhaps Kamohoaliʻi has taken a liking to its barnacle covered facade. We regretfully leave the submerged atoll and head SE into the prevailing winds and swells.

We motor towards ʻŌnūnui and Ōnūiki (Gardner Pinnacles). For the first time during our journey, we encounter ua (rain) as squalls on the distant horizon move quickly toward us. The cool ua feels refreshing on my skin, washing away the stickiness of the day. I think about the meaning of the names ʻOnūnui/ʻOnūiki as variants of the name Ununui which refers to a large altar. The name may allude to the pinnacles function as an ahu (altar) in petitioning for the northwest rains (PMNM place name map).

I marvel at the brilliance of my ancestors and their naming practices that reflect traditional ecological and cultural knowledge gained over centuries of astute observations and passed down through the generations.

We continue toward the southeast in rough seas and winds. The continual pounding of ocean against the hull is deafening and unrestrained items fly off counters and cabinets. Water continually hammers the porthole and I pray it will hold. Sleep is impossible as my cabin is in the prow of the vessel, right above the bilge. Throughout the night Iʻm lifted off the bunk, catching serious airtime. No zʻs for me on this turbulent night.

Lā ʻEono (Day 6) July 17, 2019

Lalo, Kānemilohaʻi, Mokupāpapa. These are the traditional Hawaiian names of French Frigate

Shoals.

Itʻs early morning and Iʻm catching some fresh air on the flybridge before a rain squall chases me inside. The Searcher is plowing through large swells and buffeted by brisk makani (wind). Most of us watch movies, nap or read to past the time. We arrive at Lalo/Kānemilohaʻi/Mokupāpapa in the evening and deploy the final acoustic monitor as the sun descends solemnly into the sea. We find a safe anchorage in the dark and welcome the gentle lapping of waves after two days of rough conditions. After dinner I head up to the flybridge to extend aloha to the gods and kūpuna (ancestors) of this place and notice a dark, vague triangular shape perched beyond the stern. I wonder what is?

“In 1786 two French frigate ships, the Astrolabe and the Boussole, under the

command of Count La Pérouse nearly ran aground at the shoals. On November 6,

1786 at about half past 1 AM on a calm moonlit night the Boussole mistook the

white, guano covered sides of the pinnacle for the sails of her sister ship, the

Astrolabe and steered toward her. At the last moment before running upon the

reef the crew spotted breaking waves and narrowly steered clear. The pinnacle is

named in honor of this event.”

Credit: www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/monument_features/historic_la_perouse.html

Lā ʻEhiku (Day 7) July 18, 2019

ʻO Hinaikamalama. Hina in the moon.

Wow! So much mana (spiritual power) infusing my morning. Witnessed a double rainbow arched over a full moon with La Perouse on the horizon. I head up to the flybridge to greet the gods and ancestors of this place. After my oli, a solitary manō approaches from the rear starboard side then quickly disappears. Perhaps this is Kānemilohaʻi, the shark god brother of Pele and Kamohoaliʻi, a kiaʻi (protector) of this place and for which this place is named.

At 9am the zodiac is loaded with gear and our shark researchers Paige and Brittany and Searcher crew set off. They will dive in five locations today to retrieve acoustic receivers that were deployed prior to Hurricane Walaka in October 2018. The receivers are monitoring the movement of manō (sharks) and other top predators in Lalo and will inform a deeper understanding of the ecology and food web dynamics in the monument.

While our colleagues are diligently searching for acoustic receivers, Eden and I keep ourselves busy. The Searcher has a well-appointed library of books and videos. I also try out my macro lenses and hone in on barnacle covered items onboard ship. Iʻm surprised at the intricate beauty of these organisms but there is more to them than meets the eye. Barnacles will attach to pretty much anything they come in contact with including vessel bottoms, other sea life and each other. They secrete a fast-curing cement that is among the most powerful natural glues known. Learn more about barnacles here: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/barnacles.html

Lā ʻEwalu (Day 8) July 19, 2019

ʻO na au walu o Kanaloa Haunawela noho i ka moana nui. The knowledge of Kanaloa who

lives in the ocean.

I wake up early and notice droplets of ua (rain) around my porthole. Ominous gray clouds surround us while the Searcher crew pulls up the anchor. Weʻll be motoring to another anchorage in Lalo today. The makani (wind) is brisk and the murky atmosphere remains throughout the day. Ocean conditions are rough with swells in the 10-15 foot range.

Despite the swells and rough conditions, our HIMB shark researchers set off to retrieve receivers. They have 3 days to locate the previously deployed receivers and today is Day 2. They will utilize GPS points to hone in on each location then set up a search pattern for retrieval.

Middle and Right: Diving gear ready to load into the zodiac while HIMB free-diver Paige Wernli displays her successful retrieval of an acoustic receiver. Credit: Malia Evans/NOAA/NMSF and Paige Wernli/HIMB

I spend the day on the flybridge, practicing kilo and reading about manō biology. I notice there are fewer manu (birds) than on previous days. Later in the afternoon I observe 4 large, dark birds soaring up high. Eventually one drops down, skims the surface and then perches on the ocean in front of the ship. Itʻs a kaʻupu (black footed albatross) and I am delighted to see it. After a few minutes, it unfurls magnificent long wings and takes off.

As afternoon stretches into twilight, I begin to worry about our wāhine on the zodiac. Captain Jon hasnʻt heard from them since early afternoon and I send out a pule (prayer) for their safe return. I scan the ocean, looking for the zodiac among the swells. During our journey, Iʻve come to view these young wāhine as ʻohana. I keep watch on the flybridge and spot the zodiac with all aboard as the sun descends toward the horizon. We all breathe a collective sigh of relief...

Lā ʻEiwa (Day 9) July 20, 2019

ʻO Hina pūkoʻa. ʻO Hina pūhalakoaʻa. ʻO Hina kupukupu. ʻO Hinaikamalama. These are the

multiple forms of Hina and coral.

The ocean is a stunning aquamarine this morning. Iʻm excited to dive in and get a close up view of the coral reef today. We load up the zodiac and our coxswain Gillian expertly maneuvers between the deep and shallow outcrops of coral. Sometimes she'll lift the motor and we are pulled/guided by our two wahine divers as we transit over particularly shallow clumps of reef. GPS indicates we are within 50 meters of the predator acoustic receiver so we anchor and dive in. Hūlō! Hurrah! So many iʻa (fish) that are unafraid and curious. Immersed in this wondrous underwater world, I continually swivel my head, wanting to see everything.

I marvel at the incredible diversity of fish and the multiple forms of coral that provide important habitat, hiding places and food for marine organisms and humans. In the Hawaiian creation chant Kumulipo, the simple coral polyp is the first organism to be born from the deep darkness. Coral polyps are the basic building blocks of life in the ocean. The multiple forms of coral growing together support a vast network of life and Iʻm witnessing it firsthand.

Our expert free-diver Paige locates the receiver and mooring line and we must set out to our next dive location. In the deeper waters beyond the fringing reef we see a large tiger shark swim past. PMNM is one of the last apex predator dominated coral reef ecosystems in the world and this apex predator is completely disinterested in us. We navigate through the shallow reef near Tern island and anchor in about 20' depths. The bottom is sandy and the water murky. We spot a Hawaiian monk seal and pup hauled up near the boat ramp and several others hauled out to the east. We watch cautiously as a few seals enter the ocean. Itʻs evident the underwater environment has been powerfully altered by Hurricane Walaka in October 2018. A large sand berm has been pushed up over the coral reef and the acoustic receiver can't be found. We head back to the Searcher as we will be leaving later this morning in order to get back to Honolulu in 3 days. Back onboard, we scrub all of the receivers of accumulated bio-film and barnacles.

As we take leave of this coral atoll, I feel so grateful to be here, with these accomplished women, contributing to our base of knowledge of PMNM. The data collected over time and space provides tools and strategies to better protect and conserve this incredibly significant place and the organisms that make their homes here.

To learn more about this atoll visit www.papahanaumokuakea.gov/visit/ffs.html.

Lā ʻUmi (Day 10) July 21, 2019

Hanohano wale ka ʻāina kūpuna, o nā moku lēʻīa. Honored of the land of my ancestors, the

abundant islands.

We are heading back to Oʻahu and the ocean of Kanaloa has a different feel, more powerful, relentless and wise. I think about makawalu and the multiple perspectives in which to observe, perceive, and experience this dynamic ocean, and the terrestrial and atmospheric systems of this ʻāina kūpuna. As a modern day scientist and educator I know that science and culture are not oppositional foes but mutually valid knowledge systems of inquiry, observation and testing over time and space. Our ancestors were the ultimate scientists and that tradition continues today.

How do I share this profound experience of re-connecting and interacting with this significant cultural land and seascape that most people will never visit? I will write...I will teach...I will honor and uphold the ancestral knowledge that is just as relevant today as it was 500 years ago.

Lā ʻUmikūmākahi (Day 11) July 22, 2019

Kūʻonoʻono ka lua o Kūhaimoana i ke kapa ʻehukai o Kaʻula. Rich is the pit of Kūhaimoana in

the seaspray of Kaʻula.

A spectacular sunset radiates out behind us in Papahānaumokuākea, on this our last night. As we transit past the darkened outlines of Kaʻula, Lehua, Niʻihau and Kauaʻi, lying cloaked in the twilight, we quietly return to nā kai ʻewalu, the poetic name for the main Hawaiian islands. The journey to Papahānaumokuākea has been kūʻonoʻono, so rich, on so many levels. As I transition back to Ao, I know that many of the richest moments were spent in kilo, deep observation of the natural world, the best teacher of all.

Lā ʻUmikūmālua (Day 12) July 23, 2019

ʻApakau ke kukuna i ka ʻili kai o nā kai ʻewalu. The rays of the sun spread throughout Hawaiʻi.

The morning sun shines brightly on the ocean, creating a light path as gentle swells transition us back to modernity. Buildings and homes sparkle on the flanks of the Koʻolau mountains on Oʻahu and a continual stream of gilded planes land and takeoff. A large rusty oil tanker sits off the west side waiting to be unloaded as the H-Power garbage plant spews gray emissions from the smoke stack. Google Calendar reminds me of todayʻs 8am meeting I will not be attending. Bombarded by modern society, I deeply understand why we need to permanently protect the land and seascapes of Papahānaumokuākea. There is value in protecting ecosystems for future generations. There is value in preventing rampant human exploitation of pristine natural areas. There is value in kilo, deep observation of our natural world that reminds us that we are not separate from or dominant over it. In the Kumulipo creation chant, life is born in the ocean, on the land and in the atmosphere and human beings are born later. We are the younger siblings in this dynamic universe, therefore we have a kuleana (responsibility/privilege) to mālama and take care of our elders. Hawaiian culture and values have much to teach on how to steward and co-exist harmoniously with the natural world and with each other.

Mahalo nui for reading!

Unless otherwise noted, the quotes below the dates are from Mele No Papahānaumokuākea composed by Kainani Kahaunaele and Halealoha Ayau in 2007. The mele affirms the genealogical relationship between Kānaka Maoli and this place and celebrates the outstanding cultural, natural and historic resources of PMNM.

View the words of the mele.

For more info on PMNM, please visit these websites:

https://marinesanctuary.org/sanctuary/papahanaumokuakea/

www.papahanaumokuakea.gov

www.fisheries.noaa.gov/pacific-islands/habitat-conservation/papahanaumokuakeamarine-

national-monument

All photos were collected under permits PMNM-2019-001 and PMNM-2019-011.