Latest Update on the Nihoa Millerbirds on Laysan Island

– New Hope for Critically Endangered Species

The Millerbird Translocation Project is a partnership of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and American Bird Conservancy within the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and World Heritage Site. The Monument is managed by the Departments of Interior and Commerce and the State of Hawai'i as Co-Trustees.

Undercover Footage of Laysan's Little Songbirds

April 8, 2015

By Megan Dalton

Since intensive monitoring of the translocated Millerbird population on Laysan came to an end last fall, I've been wrapping up some office work which has included reviewing photos and videos from my two field seasons on-island.

A male ulūlu niau (Nihoa Millerbird living on Laysan Island) visits his mate at their nest. A chick fledged from this nest on May 17, 2013. Credit: Megan Dalton/USFWS

Video clips of endangered Millerbirds and Laysan Finches obtained from a motion-activated trail camera were among my favorite things to revisit. Because of its ability to record footage in the absence of human observers, the trail cameras allowed us to capture some informative and amusing videos that I wanted to share with you.

Two important things to note: We were able to identify many individual Millerbirds on video by their unique color band combination. Also, in order to minimize disturbance to their nesting activity, trail cameras were set up near nests only after chicks had fledged.

A Closer Look at Millerbird Behavior

The first video is a short collection of clips showing Millerbirds singing, foraging, feeding fledglings, and collecting nest material. Toward the end, you will see a clip of a Millerbird ‘cannibalizing’ its own nest. Nest cannibalizing is when a breeding pair removes nesting material from a nest constructed during a previous nesting attempt and incorporates the material into a new nest. While this Millerbird behavior was known from past observations, it was exciting to capture on video.

Click here for a closer look at known Millerbird behavior. Video captured by Megan Dalton and edited by Greg Joder.

Caught in the Act! New Behaviors on Camera

The trail cameras caught a previously unknown behavior exhibited by both Millerbirds and Laysan Finches. We discovered that the territorial Millerbird pairs are not the only ones dismantling their previously constructed nests: Millerbirds from neighboring territories, and even Laysan Finches, were taking material from these nests too!

Also, it was not uncommon to see footage of neighboring Millerbirds perch on another pair’s nest momentarily when the resident pair was absent and appear to examine it inquisitively, almost as if they were scrutinizing or admiring its construction.

Click here for a previously unknown behavior caught on camera. Video captured by Megan Dalton and edited by Greg Joder.

Humorous Moments

Among the many videos of Millerbirds and finches going about their usual business were some clips that made us laugh. The final video is a compilation of humorous and endearing moments that includes clumsy fledglings, finches nibbling on almost everything in sight, and a very enthusiastically sun bathing Millerbird.

Maybe it is because we worked so closely with these birds that they so easily amuse us, or perhaps it is because we had very limited entertainment options out on Laysan, but we hope you enjoy these clips as much as we did. They provide a look at the personal lives of Laysan’s new Millerbirds, a somewhat different perspective on a project that stands out as one of Hawaiʻi’s outstanding bird conservation success stories.

Click here for humorous moments. Video captured and edited by Megan Dalton.

A huge thanks to friend Greg Joder who lent me his computer and helped me with the video editing process.

Megan Dalton is from Salt Lake City, Utah and has worked as an avian field biologist for several years on both the mainland and in Hawaiʻi. She just finished working on Midway Atoll, and is beginning another job studying Micronesian Megapodes in Saipan in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

There and Back Again: To Laysan with Love

October 30, 2014

By Megan Dalton

It’s a little surreal. September on Laysan just flew by, then we all left the island, and now I’m sitting at my desk at home in Salt Lake City, tapping away at the computer, not needing to swat at the previously omnipresent flies buzzing about my person. I’m not even sweating profusely, simply sitting in a chair – in fact, I’ve got a space heater at my feet and a fleece jacket on. But unforgiving flies and heat notwithstanding, I miss Laysan a lot.

I treasure my Laysan experiences. There is nothing quite like waking up in a place so vibrant, so noisy, and bustling heartily with wildlife, where every square foot of land (and sometimes air) is occupied by some sort of seabird, plant, duck, seal, crab, songbird… some of them endemic species found nowhere else in the world!

There is nothing quite like commuting to and from work among such unique traffic, and under the latest lovely sunrise or dark and foreboding storm cloud. And nothing like being a spectator with a front-row seat to the seasonal rhythms and progressions of such a place.

View video of a typical scene during sunset on Laysan, taken in April 2013. Birds seen and heard in this clip include Laysan Albatrosses, Black-footed Albatrosses, Sooty Terns, White Terns, Great Frigatebirds, Red-footed Boobies, Masked Boobies, and Bonin Petrels. Video by Megan Dalton

Laysan is one of those rare places that takes you back to a time when things were untamed and unbridled by our increasingly large human footprint, a feeling made all the more compelling by the island’s twentieth century to-the-brink-and-back story (see More Millerbirds, More Problems… if You’re a Field Biologist). I’m incredibly grateful to have spent time there.

Last Minute Developments

I’m certain, though, that Laysan and its inhabitants don’t even notice that everyone has left, and they are getting along just fine since our departure. During our last week on island, we had a couple of neat developments. The first was that, along with 10 USFWS staff and volunteers, we helped to remove all living Indian fleabane (Pluchea indica – a long-standing, dense, invasive shrub) from Laysan. Although we removed all the standing plants, there is an extensive seed bank that USFWS Refuge staff will be back to deal with in 2015. This is still exciting because the removal will give the native vegetation a chance to recolonize those areas that Pluchea used to so thoroughly dominate.

The second development was particularly exciting for the Millerbird team: during our very last island-wide survey, we found several Millerbirds in areas outside of NIMI Land for the first time!

One of my favorite pictures I took on Laysan: this Millerbird female, an original translocatee from Nihoa in 2012, is part of one of the most prolific breeding pairs on Laysan to date (with eight known successful fledglings). Here she is at the NW Bowl territory, brooding one of her growing chicks. Credit: Megan Dalton

All Millerbirds since the original 2011 and 2012 translocations to Laysan have remained in NIMI Land, or the northern part of the island that is dominated by native beach naupaka (Scaevola taccada), with the exception of a few adventurous birds in 2011 that went to the far south of the island.

Island-wide surveys have been conducted regularly to detect any movement outside of this area, but no birds were ever found in places outside the popular NIMI Land. That is until two days before our departure when, while performing our last island-wide survey, we observed one Millerbird breeding pair and at least three non-territorial individuals in a habitat comprised mostly of a different native shrub, ʻāweoweo (Chenopodium oahuense)!

Unusual sighting on Laysan: a Millerbird perched – not in naupaka – but in an ʻāweoweo shrub. Credit: Megan Dalton

A Sign of Good Things to Come

Millerbirds in ʻāweoweo is significant for a couple of reasons. First, it exemplifies the incredible amount of progress the native vegetation has shown in recent years. The Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge staff and volunteers have worked hard to help re-establish plants that disappeared after the island was denuded by rabbits a century ago, and nearly all of the ʻāweoweo present are a result of those efforts.

The second reason to be excited is that if Millerbirds are using new species such as ʻāweoweo or bunchgrass (Eragrostis variabilis), the potential for population growth on Laysan is much higher than if they remain limited to the naupaka. There is a lot of potentially suitable habitat remaining outside of NIMI Land that the Millerbirds haven’t occupied yet, and we are just waiting to see to if they decide to claim it. Seeing a few Millerbirds using ʻāweoweo is a good indication that they will! As we end the intensive study of the Millerbirds and transition to monitoring them like the other endangered bird species on Laysan, this is a very optimistic note for our departure.

Meanwhile, I’ll be here at home in my wool socks and beanie wistfully looking at our Laysan adventure pictures, wishing the Millerbirds and all their neighbors well. Laysan, thanks for having us!

Megan Dalton is from Salt Lake City, Utah and has worked as an avian field biologist for several years on both the mainland and in Hawaiʻi. She just returned from Laysan where she recently achieved her life goals of being a momentary perch for a curious Laysan Duck and tricking both of her crew mates with her Millerbird song impression.

The Thrill of the Chase: Working for a Millerbird Resight on Laysan

September 8, 2014 - September 21, 2014

By Barbara Heindl

It has been a busy two weeks since we got back to Laysan. The birds are no longer molting so they are making noise and, for the most part, cooperating and letting us collect the data we need given our limited time left on-island.

We are happy to say that we finally have a population estimate to share: about 160 Millerbirds on Laysan, more than three times the number that was originally translocated from Nihoa in 2011 and 2012!

The Art of Resighting

As we have mentioned in prior posts, a lot of our work on Millerbirds entails resighting color-banded birds. Birds are marked with a unique set of color bands on their legs so we can follow individuals and get a better idea of their breeding history, movements, and population demographics. Resighting birds is not an easy task with any species, but because of Millerbirds' secretive nature and the dense, bushy habitat they frequent, it is particularly difficult on Laysan.

A sneaky Millerbird keeps its color banded legs, and therefore its identity well hidden. Credit: Megan Dalton

After being evacuated due to the threat of a hurricane, I welcomed getting back to the familiar chase over the past weeks. Most mornings involve waking up before dawn and arriving in the core Millerbird habitat area (aka NIMI Land) in the northern part of the island just after sunrise.

These days the birds are particularly vocal, but there are still the sassy individuals who make you work to earn a resight. For instance, more often than not, I'll carefully navigate to a shrub where I heard a single chip note, only to arrive to silence: no rustling in the undergrowth, no fluttering just out of sight, nothing.

Moving ever so slightly to gain another view into the undergrowth, I look to the left, then to the right, and finally I see it in a small opening no bigger than my thumb. I see the small but wide-eyed look of a Millerbird that knows it has been caught.

It has not really been "caught," of course. Until we get a clear look at its legs to see if it is banded and if so, what color-band combination it has, we do not know which individual it is and can determine little about its history and status. It is at this point, especially with the really elusive sneaky ones, that I gingerly lie down on my stomach to try to get an eye-level view into the undergrowth where Millerbirds usually hang out.

Welcome to the Underbelly

The underbrush is a completely different world. A Red-tailed Tropicbird will chortle lightly, letting me know that if I come any closer, it will let out a shriek so intense I might end up with a temporary heart murmur.

The vegetation is thick, and choosing where to place your face for the optimal view can be a difficult decision. Once a place is selected, changing positions is costly, noisy, and just physically difficult with your face wedged between shrubby branches and your body bent and woven into other branches to minimize breaking any.

Deciding on a place is important, but this is only the beginning. A couple of seconds can feel like several minutes. My skin starts to crawl as the flies settle onto every uncovered piece of skin, licking up sweat or clustering on an earlier gift an overflying booby left on my shoulder. (Yes, feces!)

Waiting to Exhale

I start to time my breathing so as not to inhale any flies and also to blow off any that land on the tip of my nose… it has been all of 20 seconds. And then I hear it, a rustle just to the right, coming closer. I hear light hopping sounds… Millerbird? Rustling can be an indicator of a nearby Millerbird, but it can also be skinks, finches, or crabs.

Trying not to flush it the wrong direction, I hold my breath, making sure to only blink one eye at a time. Something in the periphery darts behind a broad naupaka leaf. Definitely a bird. It is still for a moment and my inner monologue starts chanting, "Come on, just a little leg, come on …" making me feel just a little bit like a pervert, but it is for science.

Then a leg slips out from the edge of the leaf. The black, stalky leg of a Laysan Finch. Not what I am looking for.

Seriously.

I would curse, except why waste a curse when the only one to hear it is a juvenile Red-tailed Tropicbird, and maybe a shearwater I haven't noticed yet? Hesitating for just a second, I settle back in, keeping tabs on the foraging finch nearby. The sound of the finch moving to my left could not be louder.

A pair of Millerbirds flutter their wings at each other, a good indication they are a pair. Credit: Megan Dalton

And then a chip note, and before I can even process where it comes from, a bird flutters into view not more than a foot away from my nose: Millerbird, an unbanded Millerbird. Then only a moment later I hear, just farther back from the Millerbird in view, a male singing lightly. He comes into view, briefly displaying his color bands nicely while the unbanded bird starts fluttering its wings and "churring," a good sign that the unbanded bird is a female and the two birds are a pair.

I note this and watch them for a second longer, and then they are gone - out of sight like it never happened, even though that finch is still foraging noisily nearby like Garfield chowing down on a pan of lasagna. I repeat the male's color combination obsessively over in my head, like a mantra, until I can write it down in my notebook.

These efforts do not all end in a double resight or even a single resight, but when they do, it is well worth the chase and the adrenaline rush afterwards.

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kauaʻi, Alaska, and across the United States’ mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.

After the Hurricanes: Life Abounds on Laysan

August 19, 2014 - September 7, 2014

By Barbara Heindl

Welcome Home

Megan and I are back on Laysan after our emergency evacuation. The only noticeable change was an unusually high debris line, indicating large swells from Hurricanes Julio, Iselle, and Genevieve, who were in the area while we were gone. Otherwise, Laysan is more or less just how we left it.

Within 48 hours, Laysan welcomed us back in the only way she knows how: with an intense heat wave enveloping both of us in a big, hot, sweaty hug. She also gifted us with unpredicted swells, numerous juvenile Laysan Finches, Wedge-tailed and Christmas Shearwaters, Brown and Black Noddies, and Millerbirds galore.

It feels like everything is welcoming us back to the island in its odd, unique way. During a swim after work on our first day, I lifted my head above water and was watching the tide moving sand back and forth beneath me. While doing this, a Blackspot Sergeant Fish jumped out of the water and grabbed at a lock of my hair that was dangling into the water. Though it startled me slightly (that is an understatement!), I am choosing to see this as a welcome back from the little fishes that usually come to nibble at our feet. Even they seem excited to have us back floating in the bay when the water is calm. Thanks Laysan, we missed you too.

Winter is Coming

It is hard to tell if it’s really as hot as it feels. It could easily be well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. Of course, it might just feel that way because we have been traveling in an ice box for the past six days: the well air-conditioned NOAA vessel, the Oscar Elton Sette.

Though it does not feel like it with the heat, and it is only just the beginning of fall, winter is on its way to Laysan. The first of what are usually winter’s north swells reached us shortly after our arrival, churning the bay in front of camp like a washing machine and encouraging resting monk seals to galumph (the actual term for forward propelling undulating seal movement) up the beach inland more than usual.

Inland the albatrosses are all gone, fledged and foraging in the Aleutians. They are wisely missing out on this heat and the large incoming swells, which would have been difficult for any new flyers to triumph over. I think flying among the large waves and spray would be fun for the adults, racing down 20–30 feet faces with speed and grace, turning upward just in time to miss the closeout, and then catching the next wave in the set.

Kids These Days

Though the albatross presence is missed, the island is by no means vacant or quiet. Young Laysan Finches that fledged while we were gone have taken over our camp, tackling the moths on the screen doors to our tents and generally being curious and underfoot. Often multiple finches will tackle a single moth, tearing it to pieces and then looking for more. You might think it would resemble the iconic scene from Lady and the Tramp, two dogs slurping up a single piece of spaghetti, meeting in the center for a kiss. Rest assured it is nothing as graceful or charming as that.

The fearless juvenile finches are so numerous that every entry into a weatherport requires a finch check: Are there any finches perched on bottom of the door? No. The top of the door? No. On the handle to the door? No. On the step in front of or perched on anything next to the door? No. Have any landed on you while you were doing the check? No. Now recheck all around the door one more time just to be sure.

Underground, the Wedge-tailed Shearwater burrows that held eggs before we left are now occupied by small fluffy chicks. The Red-footed Booby chicks that were all white fluff before we left are now a sleek grey, almost burgeoning on handsome. The Brown Noddies that were just hatching as we left are now vocal, begging to their parents at all hours of the day and night and tap dancing on rooftops while the human residents try to sleep inside.

Millerbirds Come Out to Play

Further inland in “NIMI land,” we were delighted to see that the Millerbirds were out in full action. After our first day back in the field we had three newly resighted individuals who had eluded us earlier in the tour. They now bring our known individual count to 100 birds! This is twice the number of individuals that were translocated in 2011 and 2012 combined. This number does not account for all the unmarked birds that we have been seeing either, and we hope to have that number nailed down soon to give us a more solid (and larger) population estimate for the season. But, regardless, YAY!

With three weeks of field time to do seven weeks’ worth of originally planned work, Megan and I hit the ground running, and the Millerbirds seem to be cooperating. Megan heard four male Millerbirds counter-singing with each other at one location. This is a stark contrast to the earlier leg of the tour when most birds were quiet, busy molting in new feathers.

It is an exciting time to be on Laysan, and we are more than excited to be back!

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kauaʻi, Alaska, and across the United States’ mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Should we stay or should we go now: Crews evacuated from Laysan due to forecasted hurricanes and tropical storms

August 5, 2014 - August 18, 2014

By Barbara Heindl

After a full month on Laysan biologists are still finding banded birds who have eluded them until this point. Credit: Megan Dalton

This past week we hit the halfway point of our 90-day tour on Laysan, and it showed. All of the Laysan castaways were in the groove.

We were monitoring over ten active nests and had seen a remarkable 90 birds out of the 103 that were banded as of the end of the 2013 monitoring season. Despite all the time we had already spent in ‘NIMI Land’, we were still seeing new birds including two translocated females who had been eluding us. It is an amazing feeling, to still be solving mysteries and chipping away at remaining questions despite being on island for over a month already.

Lifestyle-wise we were also in the groove. I stopped thinking about all the fresh foods I was missing during mealtime, and was delighted by new creations that seemed to come out of the woodwork. Where did this pumpkin custard come from? Beet salad? Delightful! Mango lassies? How refreshing! Living was good on Laysan.

It was in the midst of this swing that we got the news, the two tropical storms the rest of the team in the main Hawaiian Islands had been keeping an eye on, had turned into three: Iselle, Julio, and Geneviève. The three of them were tracking to our southwest, south and southeast respectively, with Julio projected to travel between Laysan and Lisianski. We were being evacuated within 24 hours by Naval vessels in the area.

Last minute packing: 24 hours till evacuation

The next 24 hours went by quickly. We immediately started backing up all our data and preparing camp not only for our imminent departure, but for the potential beat down from the forecasted storms. We filled buckets with sand to weigh down loose debris that birds had burrowed under, screwed all doors on our tents and structures shut, and tried to eat all the ‘good’ perishable food we had been saving at the bottom of our solar freezer for later in season. Not knowing if or when we would be able to return to Laysan meant there was no way to make it last. Needless to say we all ate a lot of bacon, sausage, and cheese in those last 24 hours - even the vegetarian - but in our minds it was better than seeing all that food go to waste.

During this time we were in consistent contact with the vessel that was hopefully coming to pick us up, but it was unclear how the pickup would go. We knew the ship in the area was a well-equipped Navy vessel, but would they pick us up by helicopter or boat? Did they have boats small enough to get past the barrier reef, or would we have to swim out to meet them? Would we be able to take any personal items or were there restrictions? Once they picked us up, then what? Would we wait out the storms and go back to Laysan? Would they take us to another island in the area or were we along for the ride joining them for wherever they were heading to? We tried our best to mentally and physically prepare for all the options, having our gear numbered and prioritized in case we could take only one bucket. Passports, wallets, and data made the first cut, cameras and laptops in the next, and everything else followed.

Operation Jackpot

Late in the evening on 7 August, we got the updated plan. The USS Comstock would be in the area at 3 am, we were to meet two metal hulled inflatable boats on our beach with all our gear at 07:30, and they would take us to the USS Comstock from there. They had ruled against a helicopter pickup to avoid the chance of hitting birds in the area, a very serious threat given the hundreds of thousands of nesting birds on the island at any given time… a number that we had told them of early on and that they verified en route. From there, where they were taking us was still anyone’s guess, but they said it would most likely be their current destination of Hong Kong.

The crew waits with all their gear on the beach at Laysan to be picked up by USS Comstock. Credit: Barbara Heindl

Early that morning we sadly trudged our numbered buckets down to the beach and waited to hear from the ship on our radios. It took a while to spot the carrier on the horizon, and at first glance it didn’t seem that big, certainly not that much bigger than the 180 ft NOAA vessel that had dropped us off. Not long after we got the last of our gear down to the beach we got word from the ship, they were 4 miles off the coast of the island and deploying the small boats to come and get us. USS Comstock operation “Jackpot” was already underway (their name for the mission, not ours).

After some searching we noticed two speedy vessels aimed to the north end of the island. After a little direction they reached the edge of the barrier reef and aimed south to the only decent channel through the reef and to the beach where we waited for them. The smaller of the two boats ventured inside, skillfully giving wide birth to a young monk seal swimming in the bay. Upon getting to shore we were greeted by ‘Hey! You guys want a lift? We just happen to be in the area if you do.’

We appreciated their humor, but it was a hard question for us. We were more than thankful and grateful that they had been in the area but none of the six of us (three Millerbird and three NOAA monk seal researchers) were happy to be leaving Laysan. We were happy to be safe, yes; but our work on Laysan was definitely not done and to be leaving prematurely felt a little unsettling. Regardless we met them with a smile and started passing our buckets over. They transferred our buckets to the second small boat and came back to get us.

As we sped outside of the reef and towards the ever growing USS Comstock, it was undeniably much, much larger than the NOAA vessel that had initially dropped us off on Laysan. I looked back to see our tiny island disappearing over the horizon. That view was one I hadn’t remembered getting when we were dropped off, and it was a hard view to take in not knowing, whether we would be back and if we did what shape the island would be in.

As we got closer to the USS Comstock, I remember seeing an uneasy look on one of my co-workers face, knowing that she was prone to sea sickness and the seas were not the calmest. I remember saying ‘Don’t worry, we’re close.’ But the boat kept going, Laysan getting smaller and smaller, the Comstock getting larger and larger, until finally we were alongside a giant windowless wall of the Navy vessel with only a rope ladder hanging down from a platform somewhere about halfway up the 8 story ship.

While staring up the looming wall, someone leaned out from the middle somewhere “Who’s first? You’re all being timed so make it count!” I looked down the line of the Laysan evacuees, and the designated first one up was hanging halfway off the boat, emptying out her breakfast to the fishes. The second one up was Robby, who when he realized he was next in line scaled the swinging ladder with ease. I was next, trying to think about how Robby climbed up, did he skip rungs? How did he get up so fast? What happens when you get to the top? Where was the safety briefing on this? I tried to time jumping on with the swell and clambered to the top, trying to ignore someone yelling ‘Don’t look down!’ from below. All 11 of us made it up on to the boat fine. We were welcomed by the Executive Officer who took us to the Officer’s Galley to talk to the ship medic, fill out health forms, and get coffee. At that point our destination was still up for debate, but his best guess was that we were going to Hong Kong.

So where are we going anyways?

An Osprey drops the crew off at Midway Island where they meet up with other Northwest Hawaiian Island evacuees. Credit: Darlene Olsen-Host

The next several hours went by quickly. We were treated to a hot lunch, chicken cordon bleu with fresh salad, not what I had envisioned for my first meal off of Laysan, but it was still delicious. The Captain had us up to his office for coffee and pastries and explained the whole situation. The NOAA monk seal researchers from Pearl and Hermes Atoll and Lisianski Island had been evacuated by other ships in the fleet at the same time, so there were 11 evacuees total. We were to be flown on an Osprey (a rotational winged aircraft) to the USS Makin Island to meet up with two other evacuees and then another flight to the USS San Diego to meet with the last three, and then on to our final destination - Midway Atoll.

Given the possibilities, hearing that we were headed to Midway was a relief. From there we would be able to enter and proof our Millerbird data, assist the Midway biologists surveying local Laysan Ducks, and partake in their coveted soft serve ice cream machine while we waited for the next flight to Honolulu. The next flight was scheduled for about a week and a half later.

This emergency evacuation really illustrates how remote and exposed we were while on Laysan. With a Naval fleet already in the area, it took 30 hours from when we heard the Navy was on the way till we landed foot on Midway. I can assure you no other situation would have had us off the island sooner.

Back to Laysan

While we hope Laysan weathered the storms in our absence, a part of me reflects on the timing of them and their threat to the Northwestern Hawaiian Island species. Unpredictable storms like this are one of the many reasons Millerbirds were translocated from Nihoa to Laysan to create a second population. Having multiple populations helps to ensure that one poorly timed and placed storm doesn’t take out all the remaining Millerbirds on the planet. Based on the actual path of the storms, it looks like Laysan lucked out this time and none of the storms went over the island. We are all optimistic that Laysan and the Millerbirds persevered with little trouble, and are looking forward to seeing them again soon.

We flew from Midway back to Honolulu on 19 August, and then ship back out to Laysan on a NOAA boat on 30 August. We will head back to Laysan to finish our season and see how the camp fared through the storms. All of us are extremely thankful to the US Navy and Marines who picked us up and were extremely impressed with their skill and compassion during operation “Jackpot.” Throughout the entire endeavor the Navy and Marine personnel treated with nothing short of extreme kindness and respect. Lots of thanks also goes out to all the folks on Midway who made sure we were safe and well fed during our time there, making sure that us castaways felt more than at home, and keeping us busy during our stay.

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kauaʻi, Alaska, and across the United States’ mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.

More Millerbirds, More Problems… if You’re a Field Biologist

July 22, 2014 - August 4, 2014

By Megan Dalton

Just one of many unbanded Millerbirds on Laysan currently giving the biologists headaches. Credit: Megan Dalton

I was lucky enough to be one of the Millerbird monitors for both this and last year’s tour, and one of the great things about coming back to Laysan is seeing first-hand how the Millerbird population has grown.

Over six months of intensive monitoring in summer 2013, Michelle Wilcox and I were able to confidently approximate how many Millerbirds existed on Laysan (121 adult individuals at the end of September 2013). Since the majority of the birds on the island were banded at that time, we were able to keep track of the number of breeding pairs and territories, along with their nesting successes and failures.

By the end, we felt like we knew ‘NIMI [Nihoa Millerbird] Land’ well enough that if we heard a Millerbird singing, we could guess with reasonable accuracy which individual bird it was.

Trying to Catch Up

Now, the days of knowing each individual are long gone! The Millerbirds on Laysan have been prolific while we’ve been away, and there are many up-and-coming young birds that have carved out new territories between the already established ones. However, there are even more unbanded birds wandering about, who are—rather unhelpful for a field biologist—nomadic and inconspicuous until they get old enough to claim a territory of their own.

Answering the question of how many unbanded birds there are, along with getting up to speed with all the other new developments, are proving to be the major challenges for Robby, Barbara, and me this season.

Restoring a Piece of Laysan

A rare portrait of the now extinct Laysan Millerbird and its nest in native bunchgrass. Credit: Walter K. Fisher, 1903

Laysan in its barren state, completely void of vegetation, as a result of an introduced rabbit population and their appetites, 1923. Credit: unknown

Laysan has a well-known history of ecological tragedy, specifically brought about by an introduced population of rabbits who devoured nearly all the vegetation on island in the 1910s and 1920s. I’ve been reading a lot of historical accounts lately relating to the natural state of Laysan just prior to that time period, when I imagine the island must have been near its peak abundance and vivaciousness.

One of my favorite accounts was written by Walter K. Fisher in 1903. When describing the fearlessness of birds here, particularly some of the endemic land birds, he writes:“While we sat working, not infrequently the little warbler, or Miller Bird, would perch on our table or chair backs, and the Laysan Rail and Finch would scurry about our feet in unobtrusive search for flies and bits of meat. Each day at meal-time the crimson Honey-eater [Laysan Honeycreeper] flew into the room and hunted for millers [moths].”Another favorite passage by Hugo H. Schauinsland in 1899 states:

“After dinner, if we sat outside in the shade of our cabin to be refreshed by the tradewinds after a hard day’s strenuous work, it would not be long before one of the pretty little brown birds [Laysan Millerbirds] would appear. It would alight on an available knee or perch on the back of a chair to boldly stare at us, or sometimes just to sing us its lovely song. Once, one of these brave little songsters decided to sing its favorite tune perched upon the upper edge of the open book that I held in my hands.”

A young Millerbird nestling, part of a future cohort of breeding Millerbirds on Laysan, rests on the rim of its nest. Credit: Megan Dalton

Many things have changed since then—the denuding of the island, the extinction of the endemic Laysan Millerbird, rail, and honeycreeper, along with several plant and insect species—but Laysan has also come a long way in terms of ecological restoration. Native bunchgrass, naupaka, and morning glory have recolonized the majority of the island where it once was barren, and a lot of hard work has been put into out-planting native shrubs and sedges as well as controlling and eradicating noxious weeds.

And now there’s a growing population of Millerbirds once again, the ones recently translocated from Nihoa that are now living and thriving on Laysan. I look forward to the day when future biologists tasked with surveying Millerbirds are presented with the “problem” of tracking an overwhelming number of birds, with males singing in every direction, and perhaps a Millerbird or two alighting on the edge of an open book.

A panoramic shot of Laysan’s northern interior as it looks today in 2014. This area is also known as “NIMI Land”. Credit: Barbara Heindl

Megan Dalton is from Salt Lake City, Utah and has worked as an avian field biologist for several years on both the mainland and in Hawai‘i. She is thrilled to be on Laysan again where she has recently reached her current life goals of being a momentary perch for a curious Laysan Duck and tricking both of her crew mates with her Millerbird song impression.

References:

Fisher, W. K. 1903. Notes on the Birds Peculiar to Laysan Island, Hawaiian Group. Auk 20: 384-397. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4069753.

Schauinsland, Hugo H. 1996. Three months on a coral island (Laysan), 1899. Translated by Miklos D. F. Udvardy. in Atoll Research Bulletin. 432: 1-61. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C. http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/atollresearchbulletin/issues/00432.pdf

A Tubenose's First Milestone: Facing the Air and Sea

July 5, 2014 - July 21, 2014

By Robby Kohley

We have been on Laysan for three weeks, and with camp establishment, familiarization, and general training behind us, we have settled into a daily routine that focuses on population monitoring of Millerbirds. We are just getting started but we are already excited about our initial discoveries. We have seen 73 of the 109 banded birds known from the end of the last monitoring season in September 2013. We expect this number to continue to grow as we investigate more areas.

I participated in the pre-translocation work on Nihoa in 2009 and 2010, as well as both translocations and post-release monitoring periods in 2011 and 2012, so the initial founder birds are of particular interest to me. Because of the time spent working and cheering for them, many feel like old friends. In just a short time we have already seen 25 of the 50 original founders and expect to find more.

These founding individuals continue to expand our understanding of Millerbird biology as they repopulate Laysan, with some possibly setting new longevity records for the species. Megan, Barbara, and I are excited to continue the search for more Millerbirds, and share the results in the future.

Coming of Age on Laysan: Albatross Chicks Take First Flight to Sea

An unfortunate example of the effects of being fed plastic on a young albatross. Credit: Barbara Heindl

One of the motivations for a biologist to keep returning to work on the small island of Laysan is that no matter what time of year, there is some type of exciting natural history spectacle to appreciate. This month has been no exception, with the fledging Laysan and Black-footed Albatrosses putting on a stirring show.

The albatross parents have spent 290 days, flown an estimated 50,000 combined miles, and avoided the many perils of the open ocean to get the young albatrosses to this milestone in their life—their first flight.

Unfortunately some of the perils of the open ocean that the adults must overcome in order to successfully raise young include dangerous human-made obstacles. These include thousands of hooks placed out by the long-line fisheries, which can snare and drown birds, and tons of small pieces of plastic floating on the surface of the ocean, which can be ingested directly or indirectly due to their resemblance or association with the birds’ primary food sources. The plastic can gravely affect the adults or be passed on to the young during feeding, causing death due to choking, starvation, or dehydration.

Shark attacking an unlucky young albatross that will not be making it to the far North Pacific. Credit: Robby Kohley

Shark attacking an unlucky young albatross that will not be making it to the far North Pacific. Credit: Robby Kohley

The next step is one the young albatrosses must take on their own, with no guidance from the adults, and it is a big step! They must learn to fly while safely navigating the crashing waves and avoiding the tiger sharks that have gathered just off-shore to gulp down any unlucky albatross that spends too much time sitting on the water. Immediately upon learning to fly, they must travel hundreds of miles to their central feeding grounds in the far North Pacific. This could be compared to a toddler learning to walk and immediately being made to run a marathon in order to get lunch.

A young Laysan Albatross recovers from being caught in the spin-cycle of the waves. Credit: Robby Kohley

Observing the fledging process is a captivating lesson in animal behavior and the pragmatism of nature. For young albatross, where on the island they hatch and then decide to practice flying can mean the difference between failure and success.

Practice Makes Perfect—If You’re Lucky!

Some individual young albatross practice flying at the South Ledge, which is characterized by crashing waves. Many become caught up by the waves on their first attempt, and with no easy way to escape they quickly become overwhelmed. If they do escape there is a decent chance they are injured or have used up too much energy and burned precious fat reserves that will be needed to make it north. Others, by fortunate circumstance, end up practicing on the inland lake or the calmer bays on the island. These areas allow for many short practice flights, better muscle development—and more second chances!

A young Laysan Albatross overcomes the odds and heads for the far North Pacific. Credit: Robby Kohley

While watching the young albatrosses it is hard not to feel empathy for their situation as they struggle in the waves, crash land while practicing to fly, or stand on shore staring out to sea over the breaking waves and tiger sharks, toward the horizon knowing their future is that way, with no idea what to expect. It is easy for a person to identify a time in their life when they were in comparable circumstances, when maybe you faltered while learning, failed because you weren’t prepared, or faced a big change or decision in your life with no idea what the future may hold.

This is why when you see a young albatross overcome it all and disappear over the horizon, it is hard not to crack a smile, wish him well—and want to warn him of the perils of fishhooks and floating plastic that await him.

Robby Kohley has worked on conservation projects throughout the Hawaiian Islands since 2007, most recently for the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project on their efforts to protect the endangered Akikiki and Akekeʻe. While on Laysan he hopes to capture photos of fledgling albatross and furtive Millerbirds. On his off-time, he enjoys killing black flies, stashing candy bars and sun bathing.

Fresh Meat for Flies: First Impressions of Laysan Island from a New Field Technician

July 7, 2014

By Barbara Heindl

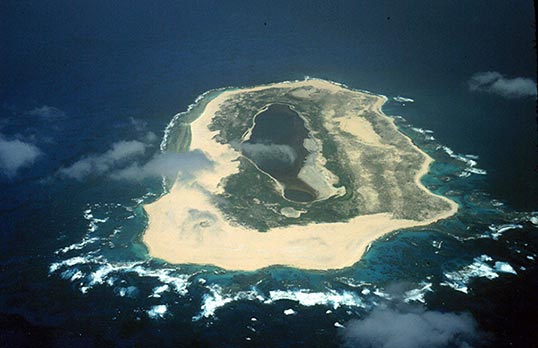

It has been a week since I arrived on Laysan Island with fellow field biologists Megan Dalton and Robby Kohley. We have been sent to Laysan, a small island in the Northwest Hawaiian chain about 930 miles northwest from Honolulu, to monitor a population of translocated Millerbirds. The last time anyone checked on the Millerbirds was in September 2013, when Megan, Michelle Wilcox, and Andrea Kristof departed (http://abcbirds.wordpress.com/2013/09/16/millerbird-drama-season-finale-on-laysan-island/).

Figure 1. The Millerbird monitoring team on Laysan (left to right): Megan Dalton, Barbara Heindl, and Robby Kohley. Laysan Albatrosses are also seen in the background. Credit: Barbara Heindl

In 2011 and 2012, a total of 50 individuals were brought from Nihoa Island to Laysan Island, where Millerbirds had been extinct on the island for almost 100 years. The original Laysan Millerbird population went extinct because of habitat degradation caused by introduced, non-native rabbits. Once the rabbits were eradicated, and decades of habitat restoration completed by USFWS Refuges, the Millerbirds were translocated.

Life in the Field: Adaptation

When you start a new field job there is always a transition period. The period of time where everything is new, your assumptions about the location and experience are either met or modified. You develop a flow with your new co-workers who are also the people you will be living with for the next several months. You are forced to compare all your new experiences to your old ones and for the most part, maybe more than anything else, are trying to cope with how to take in everything, new guidelines, new living quarters, new background noises, everything.

I am not sure whether this experience has been eased or complicated by my working almost exclusively on Kauaʻi, the closest (~800 mi) inhabited island in the main Hawaiian chain, for the last five years.

On “Gilligan’s Island”

Everything on Laysan is still part of Hawaiʻi, but at the same time different from the Hawaiʻi I have previously experienced. It is undeniably closer to what my family and friends from the mainland visualize. An ocean view backdrops every image I lay my eyes on. Gilligan’s Island is a close approximation, and the coconut wireless is real, though no one has managed to engineer an FM/AM coconut radio yet. But otherwise it is a stark contrast from the work I have been doing for the past 5 years.

Working for the Kauaʻi Forest Bird Recovery Project, my “office” was the Alakaʻi Swamp in montane rainforest at the uppermost elevations of Kauaʻi. The Alakaʻi is a tangled jungle-gym of forest where, while you may see rainbows at the end of the day, it is likely because you have just endured or are still sitting in a torrential downpour. Working there you are constantly tripped by vines and low branches, and often fight to get through dense woven masses of ʻohe naupaka or shrub ʻōhiʻa, a task that requires not only the patience of a saint but also the zen-like resolve of a monk.

Bird Detection in NIMI Land

On Laysan, in what is fondly referred to as “NIMI land” (NIMI being the field code for Nihoa Millerbird), I have traded in that familiar tangled mess of twisted shrub ʻōhiʻa for tangled beach naupaka (a native coastal shrub). The main difference being that beneath the matted naupaka are countless nesting Wedge-tailed Shearwaters, Red-tailed Tropicbirds, Brown Noddies and, of course, Nihoa Millerbirds. All of which makes every step an exercise in decision-making and a lesson on the effects of one’s footsteps on an environment not made for humans.

Figure 2. A screaming Great Frigatebird chick in its nest in the naupaka on Laysan. Credit: Barbara Heindl

Detecting Millerbirds is far more difficult then I initially expected. I am used to detecting birds, in most situations by sound first, and usually I am able to narrow the location down and get visual confirmation shortly thereafter. While the Millerbird song and calls are distinct, they are fragile and can be hard to pick out through the deafening din of Great Frigatebird and Red-footed Booby nestlings begging for food. Sooty Terns and Noddies swooping above you don’t help either while you are trying to focus on the mouse-sized Millerbirds secretively hopping around the underbrush.

On Kauaʻi a “busy” bird survey might become more difficult if you are flanked by a single upset Kauaʻi ʻElepaio or a chatty Japanese White-eye, both which might make detecting the ever-decreasing ʻAkikiki or ʻAkekeʻe difficult. These distractions are nowhere near the cacophonous sound of upset seabirds and hoards of flies buzzing in your ears, eyes, and nose. Even keeping in mind that the Millerbird is only one of two songbirds on the island, the social and consistent melody of the Laysan Finch can easily cover and mask a nearby Millerbird’s gentle “chk chk” call as well.

Toward a Future with Many Millerbirds

I have been repeatedly amazed and so thankful to be joined in the field with Millerbird veterans Robby and Megan. They both have been involved at critical stages of the Nihoa Millerbird project, including the two translocations and the transition to monitoring the growth and success of the new population.

Their skill and proficiency in this environment is not only impressive, but has also been a valuable resource for me in learning the ropes during our first week on the island. They can detect the light song of a Millerbird tens of meters away, when all I hear are the primordial shrieks of Frigatebirds directly above us.

The few interactions I’ve had with Millerbirds so far have been deeply rewarding, all thanks to these two seasoned biologists. I’m looking forward to seeing what the next three months bring, especially as I start to get my feet under me in the field, both figuratively and metaphorically. Whatever the future brings, here’s to hoping there are lots of Millerbirds in it!

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi, Alaska, and across the United States’ mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View 2013 Updates.

View 2012 Updates.

View 2011 Updates.

Click Here for photos, videos and more information (you will be directed to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service website).