First Two Days at Sea and Entry Into Papahānaumokuākea

The first few days on the ship are a whirlwind of familiarization including shipboard protocol and procedure, safety and dive training, neurological exams, proper behavior on ship; we even discuss what to wear in the mess hall (shipboard dining room) – no hats, tank tops, or water gear. After frenetic preparations prior to departure, much of which involves extensive packing, provisioning, and travel from across Hawaiʻi and even the world, we are all tired. These first few days getting accustomed to being at sea are both a relief for finally heading out and disorienting, as we get accustomed to living on a 224 ft. ship. We are plunged into another world, not much different than heading into space except our world is a water world.

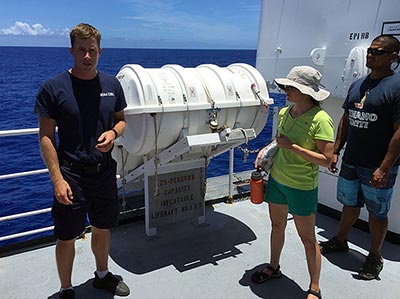

Some drills are more challenging than others. The abandoned ship drill in particular is both the goofiest and the most uncomfortable. Even in the warm waters of Hawaiʻi (about 81° F) a person can die from hypothermia over time. How much time depends on a number of factors including body fat content and how much of the body is submerged. In really cold waters (41° F) a ballpark estimate is that a person can survive for 15-20 minutes. To protect against this hazard, every crewmember is issued a red survival suit, affectionately called a “gumby suit.” Today the ship called an abandoned ship drill and we all had to grab our lifejackets, ditch bag clothing, survival suits and head to our assigned stations. Across the ship people were scrambling to get to their staterooms, grab their gear, and head up to their stations, which can be three or four decks above the staterooms. Once we arrived at our stations, we had to demonstrate that we could get into our survival suits. Picture 40 people sweating in the hot sun and griddle-like deck of the rolling ship while awkwardly contorting themselves into heavy, red neoprene suits. It is a goofy, but necessary exercise so we know what to do in the unlikely event that the ship starts to sink. We also reviewed the procedure for launching the life rafts.

Other training included the procedure for addressing a dive accident, or injury while in the field. The science party practiced working with the oxygen kits, and how to administer oxygen to a diver in the unlikely event of a dive accident and decompression sickness. Dive accidents can happen to anyone, since diving is an inherently risky practice, but generally are associated with coming to the surface too quickly and the nitrogen gas accumulated in the bloodstream comes out of solution and forms gas bubbles that can cause problems. Since we are so far away from any hospital, the ship carries a decompression chamber to treat and stabilize any dive accident patient. The chamber is a large metal tube that pressurizes the air and essentially brings the dive accident victim back down to a certain depth (starting at 60 feet) where the nitrogen bubbles causing the issues are “compressed” back into solution in the bloodstream. The patient then remains in the chamber breathing 100% oxygen for long enough to allow the body’s natural off-gassing ability to safely remove the excess nitrogen. Once the process is started, no matter the level of the injury, the diver must stay in the chamber for a minimum of six hours. We do not expect to have to use the chamber, since diving is carried out with stringent safety protocols, but the ship and crew are prepared for most emergencies.

I’m going to tell you three words, and after you are done reading this – and without cheating – repeat them back to me: apple, snowflake, dump truck. This is how the neurological examination starts with the onboard Public Health Service Commissioned Corps Officer LT Ryan Hawley. Since NOAA, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and many other U.S. public agencies do not have medical staff of their own they rely on the U.S. Public Health Service (http://www.usphs.gov) to provide medical professionals for ships at sea, and many American Indian reservations that do not have their own health services. In addition to pre-departure medical clearance with the NOAA Health Services, an onboard neurological exam is administered to all divers and snorkelers working from the small boats. The purpose of this exam is to identify any existing issues with neurological function (brain, nerve and motor function) and to set a baseline to compare against if an accident does happen that impacts the ability to have full motion in an arm, or reflexes, or skin sensitivity. A baseline is also set for memory recall – do you remember the three words? No cheating!

Many of these drills and exams sound ominous, but the purpose is to be prepared and have the information we need in the unlikely event of an emergency or injury. In this way it really is not much different from being in space. By necessity and distance we need to be self-reliant.

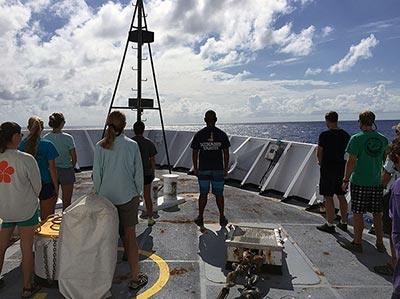

We crossed the boundary of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument today and conducted an entry protocol with a series of chants, ending in Mele no Papahānaumokuākea. This unique “name song” was written for this special place by Kainani Kahaunaele and Halealoha Ayau in the year the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument was given the name Papahānaumokuākea. We all feel very blessed to have the opportunity to work within this incredible place.

Return to RAMP Expedition Log.